Katherine Boyle and David Ulevitch are both venture capitalists with mega VC firm Andreessen Horowitz, and both have been outspoken on the role that VC should play in the broader economy.

The firm has taken it so far as to create an “American Dynamism” practice, headed by Boyle, that’s tasked with investing in founders and companies that support the national interest, including those in aerospace, defense, education, housing, transportation, public safety, supply chain, industrials, and manufacturing.

Per a16z: “We believe these areas represent tremendous venture-scale opportunities. More importantly, these categories serve as a critical foundation to making America the country people want to be from, immigrate to, and build a life and career or company in.”

That was in January 2022. In May 2023 they came back with a new take on this topic in the WSJ, announcing a $500 million commitment to fund early-stage companies that "support the national interest."

The program is designed to more closely connect Washington to the tech world, and vice versa, so that America’s problem solvers are all moving in the same direction.

"We want to send out a signal [to entrepreneurs] that they don't have to be building a consumer company in Silicon Valley to get the interest of venture capitalists," David Ulevitch, co-leader of the practice, told Axios.

The short story in this announcement is that entrepreneurs can have an outsized impact on the direction of the country compared to policymakers, enterprises and others.

Will it work? Maybe. Seems well intentioned and a worthwhile step from a major player in VC. But downturns always reveal the truth, so whether or not this turns into a major trend remains to be seen.

It's interesting to me that this effort is coming together alongside the recent announcement that BlackRock would be shifting its attention, if not its dollars, away from ESG, which encompasses a range of ethically responsible business practices, shifting course from the firms' 2018 pledge to add "social purpose" to its investment decisions. Not a surprise given how politically politicized that has become (and don't get me started on that).

As BlackRock CEO Larry Fink said at the time: "I don't use the word ESG any more, because it's been entirely weaponised ... by the far left and weaponised by the far right." … "We had one of the best years ever, but I'm ashamed of being part of this conversation," adding that his annual letters to investors that addressed ESG issues were never meant to be political statements.

And, while the fund says it remains committed to decarbonization, corporate governance, climate change and social issues, it did recently name Amin Nasser, the CEO of Saudi Arabia’s oil company Aramco, to its board.

Regardless what’s happening at the investor level, I wonder if there's something new coalescing around this broader idea of impact and why businesses exist. Because the full "make a difference with your startup" story is a little bit more nuanced. Supporting innovation, creating jobs, etc have long been the selling point for broad support of entrepreneurs.

Does that still stand up?

Job Creation

As I wrote a few weeks back, the line from the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation has long been that firms less than five years old account for nearly all net new jobs in the U.S. And for years that data held up.

From 1980-2005, nearly all net job creation in the United States occurred in firms less than five years old. Without startups, net job creation for the American economy would be negative in all but a handful of years. Excluding startups, an analysis of the 2007 Census data shows that firms less than five years old still accounted for roughly two-thirds of job creation. “Of the overall 12 million new jobs added in 2007, young firms were responsible for the creation of nearly 8 million of those jobs.”

“Given this information, it is clear that new and young companies and the entrepreneurs that create them are the engines of job creation and eventual economic recovery. The distinction of firm age, not necessarily size, as the driver of job creation has many implications, particularly for policymakers who are focusing on small business as the answer to a dire employment situation.”

Great news, but the story has changed since that research came out a decade-plus ago.

Young companies continue to create new jobs, but the rate of growth has slowed dramatically due to the number of jobs that these firms support. Today’s startups are rarely in manufacturing or brick-and-mortar services where it’s important to have large staffs to support operations. Nimble is the name of the game, and it turns out there you don’t need too many people working for you once you’ve maximized your efficiency.

Case in point, the pandemic darling Zoom saw more than 800 million monthly users as recently as April 2023 (it hit nearly a billion per month a few times at the height of Covid). An impressive achievement, especially given that the company only employees about 2,500 people worldwide.

Per Kauffman circa 2022: “Over the past several decades, there is evidence that job creation among new firms has declined — as has the share of U.S. employment attributable to these young firms. Startups are now creating fewer jobs than they did a quarter century ago, and fewer business applications today are resulting in new employer businesses than they did 15 years ago.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, a spike in business applications was accompanied by a decrease in the proportion of applications for businesses that were likely to become employers and create jobs for anyone other than the entrepreneurs themselves. These trends raise important questions about the ability of young firms to continue to create new jobs today — and the extent to which they will be able to do so in the future.”

As of 2021, the average U.S. startup created 4.74 jobs during its first year of operation. That’s down from over 7.6 in 1996. And the drop off is hard to ignore.

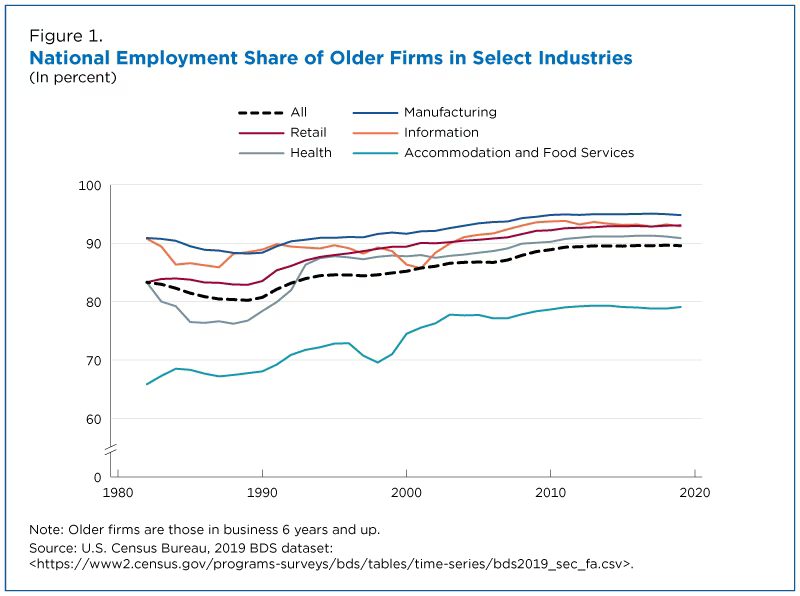

Short story: Startups create new jobs, but most people now work at older companies.

Investing in Innovation

Startups and the VC ecosystem tend to get a lot of credit for broadly supporting innovation, picking up the role that corporate R&D departments used to dominate in developing new technologies. The simple fact is that growth in corporate R&D has stagnated in recent decades and enterprises looked to cut costs and run more efficient operations, instead looking outside for innovations. Corporates have spent the last few decades ignoring their own internal innovation departments and now have no choice but to shop for the latest technologies, the newest developments and the cutting edge insights at smart startups.

And, if we look solely at the investment numbers, this storyline looks to hold up.

Venture capital investment in the U.S. set a record in 2021, reaching nearly $345 billion and doubling the haul during 2020 (dropping to $240B in 2022). But those investment dollars weren’t evenly distributed throughout the economy.

Value of venture capital (VC) investment in the United States in 2022, by industry(in billion U.S. dollars)

Add it up, and roughly 65% of all U.S. venture funding in 2022 went to just three industries — software, B2B and pharmaceuticals / biotech. Take it a step further and more than 37% went to software alone.

That’s a lot of also-ran capital and a pretty thin pool of innovation.

Worse, more and more funding is going to later stage deals where positive returns are more likely on the typical 10-year VC timeline. That’s leaving less available to new, cutting edge startups and further breaking the innovation storyline.

What am I missing?

Fact is, venture and the startup economy are going through a reckoning right now, and it’s not clear what will be left standing right now. VC funding and fundraising are down sharply, investment rounds have quieted, and many funds are sitting on the sidelines until things quiet down.

Maybe there was too much hype. Maybe there was too much money thrown at losing ideas. And maybe too many people bought into it for too long. Whatever the case, downturns like this tend to expose the weak while bolstering the strong.

It’s like Warren Buffett said: “Only when the tide goes out do you learn who has been swimming naked.”

That might end up being a good thing for the startup economy, helping to get things back on track.